Welcome to Raja Ampat

Below is articles (Chatper 35 only) from a book : "The Malay Archipelago" by Alfred Russel Wallace.

The Malay Archipelago is a book by the British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace that chronicles his scientific exploration, during the eight year period 1854 to 1862, of the southern portion of the Malay Archipelago including Malaysia, Singapore, the islands of Indonesia, and the island of New Guinea. Its full title was The Malay Archipelago: The land of the orang-utan, and the bird of paradise. A narrative of travel, with sketches of man and nature.

Complete info about this book visit :

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Malay_Archipelago

CHAPTER XXXV :

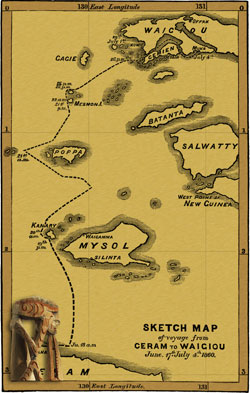

VOYAGE FROM CERAM TO WAIGIOU (JUNE AND JULY 1860)

IN my twenty-fifth chapter I have described my arrival at Wahai, on my way to Mysol and Waigiou, islands which belong to the Papuan district, and the account of which naturally follows after that of my visit to the mainland of New Guinea. I now take up my narrative at my departure from Wahai, with the intention of carrying various necessary stores to my assistant, Mr. Allen, at Silinta, in Mysol, and then continuing my journey to Waigiou. It will be remembered that I was travelling in a small prau, which I had purchased and fitted up in Goram, and that, having been deserted by my crew on the coast of Ceram, I had obtained four men at Wahai, who, with my Amboynese hunter, constituted my crew.

Between Ceram and Mysol there are sixty miles of open sea, and along this wide channel the east monsoon blows strongly; so that with native praus, which will not lay up to the wind, it requires some care in crossing. In order to give ourselves sufficient leeway, we sailed back from Wahai eastward, along the coast of Ceram, with the land-breeze; but in the morning (June 18th) had not gone nearly so far as I expected. My pilot, an old and experienced sailor, named Gurulampoko, assured me there was a current setting to the eastward, and that we could easily lay across to Silinta, in Mysol. As we got out from the land the wind increased, and there was a considerable sea, which made my short little vessel plunge and roll about violently. By sunset -we had not got halfway across, but could see Mysol distinctly. All night we went along uneasily, and at daybreak, on looking out anxiously, I found that we had fallen much to the westward during the night, owing, no doubt, to the pilot being sleepy and not keeping the boat sufficiently close to the wind. We could see the mountains distinctly, but it was clear we should not reach Silinta, and should have some difficulty in getting to the extreme westward point of the island. The sea was now very boisterous, and our prau was continually beaten to leeward by the waves, and after another weary day we found w e could not get to Mysol at all, but might perhaps reach the island called Pulo Kanary, about ten miles to the north-west. Thence we might await a favourable wind to reach Waigamma, on the north side of the island, and visit Allen by means of a small boat.

About nine o'clock at night, greatly to my satisfaction, we got under the lea of this island, into quite smooth water--for I had been very sick and uncomfortable, and had eaten scarcely anything since the preceding morning. We were slowly nearing the shore, which the smooth dark water told us we could safely approach; and were congratulating ourselves on soon being at anchor, with the prospect of hot coffee, a good supper, and a sound sleep, when the wind completely dropped, and we had to get out the oars to row. We were not more than two hundred yards from the shore, when I noticed that we seemed to get no nearer although the men were rowing hard, but drifted to the westward, and the prau would not obey the helm, but continually fell off, and gave us much trouble to bring her up again. Soon a laud ripple of water told us we were seized by one of those treacherous currents which so frequently frustrate all the efforts of the voyager in these seas; the men threw down the oars in despair, and in a few minutes we drifted to leeward of the island fairly out to sea again, and lost our last chance of ever reaching Mysol! Hoisting our jib, we lay to, and in the morning found ourselves only a few miles from the island, but wit, such a steady wind blowing from its direction as to render it impossible for us to get back to it.

We now made sail to the northward, hoping soon to get a more southerly wind. Towards noon the sea was much smoother, and with a S.S.E. wind we were laying in the direction of Salwatty, which I hoped to reach, as I could there easily get a boat to take provisions and stores to my companion in Mysol. This wind did not, however, last long, but died away into a calm; and a light west wind springing up, with a dark bank of clouds, again gave us hopes of reaching Mysol. We were soon, however, again disappointed. The E.S.E. wind began to blow again with violence, and continued all night in irregular gusts, and with a short cross sea tossed us about unmercifully, and so continually took our sails aback, that we were at length forced to run before it with our jib only, to escape being swamped by our heavy mainsail. After another miserable and anxious night, we found that we had drifted westward of the island of Poppa, and the wind being again a little southerly, we made all sail in order to reach it. This we did not succeed in doing, passing to the north-west, when the wind again blew hard from the E.S.E., and our last hope of finding a refuge till better weather was frustrated. This was a very serious matter to me, as I could not tell how Charles Allen might act, if, after waiting in vain for me, he should return to Wahai, and find that I had left there long before, and had not since been heard of. Such an event as our missing an island forty miles long would hardly occur to him, and he would conclude either that our boat had foundered, or that my crew had murdered me and run away with her. However, as it was physically impossible now for me to reach him, the only thing to be done was to make the best of my way to Waigiou, and trust to our meeting some traders, who might convey to him the news of my safety.

Finding on my map a group of three small islands, twenty-five miles north of Poppa, I resolved, if possible, to rest there a day or two. We could lay our boat's head N.E. by N.; but a heavy sea from the eastward so continually beat us off our course, and we made so much leeway, that I found it would be as much as we could do to reach them. It was a delicate point to keep our head in the best direction, neither so close to the wind as to stop our way, or so free as to carry us too far to leeward. I continually directed the steersman myself, and by incessant vigilance succeeded, just at sunset, in bringing our boat to an anchor under the lee of the southern point of one of the islands. The anchorage was, however, by no means good, there being a fringing coral reef, dry at low water, beyond which, on a bottom strewn with masses of coral, we were obliged to anchor. We had now been incessantly tossing about for four days in our small undecked boat, with constant disappointments and anxiety, and it was a great comfort to have a night of quiet and comparative safety. My old pilot had never left the helm for more than an hour at a time, when one of the others would relieve him for a little sleep; so I determined the next morning to look out for a secure and convenient harbour, and rest on shore for a day.

In the morning, finding it would be necessary for us to get round a rocky point, I wanted my men to go on shore and cut jungle- rope, by which to secure us from being again drafted away, as the wind was directly off shore. I unfortunately, however, allowed myself to be overruled by the pilot and crew, who all declared that it was the easiest thing possible, and that they would row the boat round the point in a few minutes. They accordingly got up the anchor, set the jib, and began rowing; but, just as I had feared, we drifted rapidly off shore, and had to drop anchor again in deeper water, and much farther off. The two best men, a Papuan and a Malay now swam on shore, each carrying a hatchet, and went into the jungle to seek creepers for rope. After about an hour our anchor loosed hold, and began to drag. This alarmed me greatly, and we let go our spare anchor, and, by running out all our cable, appeared tolerably secure again. We were now most anxious for the return of the men, and were going to fire our muskets to recall them, when we observed them on the beach, some way off, and almost immediately our anchors again slipped, and we drifted slowly away into deep water. We instantly seized the oars, but found we could not counteract the wind and current, and our frantic cries to the men were not heard till we had got a long way off; as they seemed to be hunting for shell-fish on the beach. Very soon, however, they stared at us, and in a few minutes seemed to comprehend their situation; for they rushed down into the water, as if to swim off, but again returned on shore, as if afraid to make the attempt. We had drawn up our anchors at first not to check our rowing; but now, finding we could do nothing, we let them both hang down by the full length of the cables. This stopped our way very much, and we drifted from shore very slowly, and hoped the men would hastily form a raft, or cut down a soft-wood tree, and paddle out, to us, as we were still not more than a third of a mile from shore. They seemed, however, to have half lost their senses, gesticulating wildly to us, running along the beach, then going unto the forest; and just when we thought they had prepared some mode of making an attempt to reach us, we saw the smoke of a fire they had made to cook their shell-fish! They had evidently given up all idea of coming after us, and we were obliged to look to our own position.

We were now about a mile from shore, and midway between two of the islands, but we were slowly drifting out, to sea to the westward, and our only chance of yet saving the men was to reach the opposite shore. We therefore sot our jib and rowed hard; but the wind failed, and we drifted out so rapidly that we had some difficulty in reaching the extreme westerly point of the island. Our only sailor left, then swam ashore with a rope, and helped to tow us round the point into a tolerably safe and secure anchorage, well sheltered from the wind, but exposed to a little swell which jerked our anchor and made us rather uneasy. We were now in a sad plight, having lost our two best men, and being doubtful if we had strength left to hoist our mainsail. We had only two days' water on board, and the small, rocky, volcanic island did not promise us much chance of finding any. The conduct of the men on shore was such as to render it doubtful if they would make any serious attempt to reach us, though they might easily do so, having two good choppers, with which in a day they could male a small outrigger raft on which they could safely cross the two miles of smooth sea with the wind right aft, if they started from the east end of the island, so as to allow for the current. I could only hope they would be sensible enough to make the attempt, and determined to stay as long as I could to give them the chance.

We passed an anxious night, fearful of again breaking our anchor or rattan cable. In the morning (23rd), finding all secure, I waded on shore with my two men, leaving the old steersman and the cook on board, with a loaded musketto recall us if needed. We first walked along the beach, till stopped by the vertical cliffs at the east end of the island, finding a place where meat had been smoked, a turtle-shell still greasy, and some cut wood, the leaves of which were still green, showing that some boat had been here very recently. We then entered the jungle, cutting our way up to the top of the hill, but when we got there could see nothing, owing to the thickness of the forest. Returning, we cut some bamboos, and sharpened them to dig for water in a low spot where some sago -trees were growing; when, just as we were going to begin, Hoi, the Wahai man, called out to say he had found water. It was a deep hole among the Sago trees, in stiff black clay, full of water, which was fresh, but smelt horribly from the quantity of dead leaves and sago refuse that had fallen in. Hastily concluding that it was a spring, or that the water had filtered in, we baled it all out as well as a dozen or twenty buckets of mud and rubbish, hoping by night to have a good supply of clean water. I then went on board to breakfast, leaving my two men to make a bamboo raft to carry us on shore and back without wading. I had scarcely finished when our cable broke, and we bumped against the rocks. Luckily it was smooth and calm, and no damage was done. We searched for and got up our anchor, and found teat the cable had been cut by grating all night upon the coral. Had it given way in the night, we might have drifted out to sea without our anchor, or been seriously damaged. In the evening we went to fetch water from the well, when, greatly to our dismay, we found nothing but a little liquid mud at the bottom, and it then became evident that the hole was one which had been made to collect rain water, and would never fill again as long as the present drought continued. As we did not know what we might suffer for want of water, we filled our jar with this muddy stuff so that it might settle. In the afternoon I crossed over to the other side of the island, and made a large fire, in order that our men might see we were still there.

The next day (24th) I determined to have another search for water; and when the tide was out rounded a rocky point and went to the extremity of the island without finding any sign of the smallest stream. On our way back, noticing a very small dry bed of a watercourse, I went up it to explore, although everything was so dry that my men loudly declared it was useless to expect water there; but a little way up I was rewarded by finding a few pints in a small pool. We searched higher up in every hole and channel where water marks appeared, but could find not a drop more. Sending one of my men for a large jar and teacup, we searched along the beach till we found signs of another dry watercourse, and on ascending this were so fortunate as to discover two deep sheltered rock-holes containing several gallons of water, enough to fill all our jars. When the cup came we enjoyed a good drink of the cool pure water, and before we left had carried away, I believe, every drop on the island.

In the evening a good-sized prau appeared in sight, making apparently for the island where our men were left, and we had some hopes they might be seen and picked up, but it passed along mid-channel, and did not notice the signals we tried to make. I was now, however, pretty easy as to the fate of the men. There was plenty of sago on our rocky island, and there world probably be some on the fiat one they were left on. They had choppers, and could cut down a tree and make sago, and would most likely find sufficient water by digging. Shell-fish were abundant, and they would be able to manage very well till some boat should touch there, or till I could send and fetch them. The next day we devoted to cutting wood, filling up our jars with all the water we could find, and making ready to sail in the evening. I shot a small lory closely resembling a common species at Ternate, and a glossy starling which differed from the allied birds of Ceram and Matabello. Large wood-pigeons and crows were the only other birds I saw, but I did not obtain specimens.

Learn to Cook Papeda at Weriagar District, West Papua

Weriagar is a district located in Teluk Bintuni Regency, West Papua Province, Indonesia. The staple food of the local Weriagar community is Papeda. Papeda is made from sago cooked in boiling water on a stove until the dough looks like glue. Papeda is delicious eaten with fish in soup. Sayur bunga pepaya (papaya flower bud vegetables) and tumis kangkung (stir-fried water spinach) are often served as side-dish vegetables to accompany papeda. On some coasts and lowlands on Papua, sago is the main ingredient to all the foods. Sagu bakar, sagu…

Tanjung Kasuari, Sorong

Tanjung Kasuari beach is located in Sorong city, West Papua. This tourism object is becomes one of the most visited tourism objects in Sorong and it has been visited almost everyday. It located around 7Km from down town of Sorong city, and it can be reach by using private vehicle or public transportation. The nuance in this beach is windy and it has white sandy path along the beach, the clear water and coconut trees along the area. It so refreshing and tropical alike. Moreover, the visitors can enjoy the sunset…

Nusrowi Island, The Exotic One On West Papua

Nusrowi Island is located on the west of Rumberpon island, Wondama Bay district. This small island has an area of ??approximately 4 hectares and surrounded by shallow waters and filled with coral reefs and many species of ornamental fish. You can also see other marine commodities like grouper, sea cucumbers and lobsters. In this place you can do your favorite activities such as diving, coral reef observations and fishing; to get to this place from Ransiki to a location, we can use a longboat which takes about 1.5 hours. www.Indonesia-Tourism.com

Amazingly Fak Fak

Fak Fak This district is famous for the agriculture plant of nutmeg, which make this city known as “Kota Pala” or the city of nutmeg. Fakfak regency is one of the oldest cities in Papua, with a high civilization. Historically Fakfak was a significant port town, being one of the few Papuan towns that had relations with the Sultanate of Ternate, being bound to it. The Sultanate later granted the Dutch colonial government permission to settle in Papua, including in Fakfak. The Dutch began the settlement in 1898. The town…